|

|

| |||||||||

| The Alexandra Palace Organ Appeal | |||||||||

| Registered Charity No.:285222, London N22 7AY | |||||||||

|

| Welcome |

| News |

| People |

| The Friends |

| History |

| Barwell |

| FAQs |

|

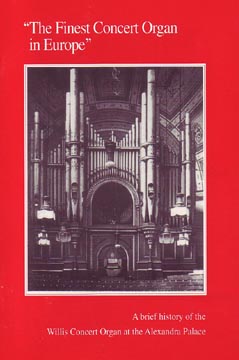

"The Finest Concert Organ in Europe"

A Brief History of The Willis Concert Organ at the Alexandra Palace Preface to the Second Edition.WE WOULD NOT PRESUME to alter one word of the content of the work of the late Ivan Barwell. His over-riding passion in life was the Alexandra Palace organ, to which he devoted many thousands of hours, to research, writing to supporters (and opponents) and long, long interviews with anyone who would listen to him.Unhappily, he never had the joy, granted to us, of hearing this great instrument sound again; but to the day he died he was certain that it should once again become "The finest Concert Organ in Europe". Those who worked with him for half a century in this aim, are carrying on towards the completion of the work, and while so many of his early supporters are no longer with us, we do have the benefit of new support from younger and more energetic helpers. For them we reproduce Ivan Barwell's booklet, now long out of print, to which we have added a summary of events, to bring the situation up-to-date. With this knowledge, we are sure that you will want to work with us towards the completion of the restoration of the Alexandra Palace Concert Organ. FELIX APRAHAMIAN FRED CLARKE DAVID WYLD JANUARY 1993 A TOWERING ORGAN reaching to the roof of The Great Hall, one hundred feet in height; and from a tiny door on the left of the gigantic instrument, emerges the diminutive, frock-coated figure of a man whose quick steps take him to the console. Once there, the little figure bows to the applauding audience far below him, slides deftly on to the bench, and arranges his frock coat so that its skirts fall over the green canvas which conceals the pedals. The year is probably 1907; and G. D. Cunningham is about to give an organ recital at the Alexandra Palace. From a child's point of view, and at so great a distance, Mr. Cunningham looks quite old, but in fact, he is in his late twenties. Each week he gives at least one recital, the best attended being those on Sunday afternoons. A local boy, educated locally, George Dorrington Cunningham had been appointed the Alexandra Palace organist at the age of twenty-three, when the Park and Palace were saved for the people and Father Willis's masterpiece (his finest concert organ) was assured of its continued existence in the unique auditorium for which, in 1875, it had been designed. Writing in 1929, Cunningham recalls what this meant to him, then still a student at the Royal Academy of Music. What it meant to the Alexandra Palace Trustees and the thousands of visitors from far and near, who attended the recitals, is well known; for here was the perfect combination of youthful master and superlative instrument. It is pleasant to recall that the organ was a mere three years the senior in this partnership. Surely Providence had intended they should meet? It certainly seems so; and the organ and its player did much to enhance the reputation and goodwill which the forward policy of the early Trustees so consistently nourished. In those first fourteen years of the Trust there was much music at the Palace, and the organ had a wider role than that of a recital instrument. The splendid Choral and Orchestral Society, soon acknowledged to be the finest in the capital, gave the first London performances of Elgar's `The Apostles' and its sequel `The Kingdom' under its conductor, Allen Gill. Possibly the composer was present at one of these performances, for he was accustomed to visit his friend, A. J. Jaeger (`Nimrod', of the `Enigma Variations') who lived in Rosebery Road, hard by the Palace. Organ support was frequently needed in popular concerts, of course. The Massed Bands of the Brigade of Guards were re-enforced by Cunningham at his great instrument in Tchaikovsky's overture, `1812' - with, be it said, heavy pyrotechnic embellishments. And so it was, that year in and year out, the Palace Organ played its part in the nation's music-making; for it must be remembered that the Alexandra Palace was the home of large festivals. And then there was Clara Butt - almost a festival in herself! She needed the organ to accompany her in `Abide with Me' and Handel's Largo. Once she nearly had no organ, her accompanist got no response from the great instrument. After some delay, the singer's voice boomed forth a challenge: `Is there nobody here who understands this organ?' There was. He was sitting out in front and, leaving his seat, he went round to put things right. It was Cunningham. `At this time' says Henry Willis 3, `the organ was just `carrying on'; its mechanism, particularly its leather-work, was in a bad state. Only such attendance and repair as was essential could be afforded.' But, even though its wind was derived from bellows driven by steam engines, far down in the basement, it was rare for the grand old instrument to fail. On one occasion though, it is reported that, in the absence of the engineer, steam blew off and entered the organ which - to quote the builder's grandson again -`had to be opened up to dry out.' Of course, time had to be allowed for the raising of steam before the organ could be brought into use, either for playing or tuning, and it was customary to give twenty-four hours notice if the instrument were to have breath. By 1914 the Alexandra Palace was doing very well. Thousands visited it for countless reasons. This was the year that the young master George Thalben-Ball won a gold medal for piano-playing at the Herts. and Middlesex Music Festival at the Palace; and this was the year when all sorts of developments were being planned by the Honorary Manager, Alderman Sloper, and his fellow Trustees. But with the coming of the last Bank Holiday of that momentous summer, an era was eclipsed by an epoch so hideous that, to many, the memory is like that of a sinister dream. Not that the August Bank Holiday crowds at the Alexandra Palace realised what war was to mean. Few indeed had the foresight to realise that, in any walk of life. On that August Bank Holiday when, according to slang usage, `the balloon went up' in Europe, there was no balloon ascent at the Palace. The War Office would not allow it. A few hours later, war with Germany was declared. And so it was that those Bank Holiday crowds, from all over London, were the last members of the public to hear Father Willis's masterpiece for fifteen years. What happened during that decade- and- a-half - that `child's lifetime'? A few days after the Park had been closed for the purposes of mobilisation, the Palace became the focus for thousands of Belgian refugees, who were visited by Queen Mary before being dispersed to other centres as the weeks passed. Then came those who had driven these wretched, bemused occupants from their homeland: German prisoners of war. And then, when these were gone to prison camps, came more Germans: civilian internees. Many of these were musical, and many indeed were professional musicians from the London theatres. And so music returned to the Palace again, but the public were not allowed to hear it. The public, in fact, could not pass the armed guards at the gates. In those early days of war, steam was raised on several occasions so that Cunningham might play upon his beloved organ; but after a time his rare visits ceased.... The Great Hall, like the rest of the Palace, was in constant use; and the silent organ looked down upon a vast dormitory, while from the area at the back of the Great Orchestra, the fumes of numerous oil stoves discharged heavy particles of carbon at organ level. The cement floor upon which these stoves stood may be seen to this day. The organ then was kept warm. And not merely by the cooking stoves. There were hundreds of blankets playing their part in choking the organ pipes and mechanism in dust. This fluff, combining with the oily deposit from the stoves, was adhering to every part of the instrument when, in 1919, Cunningham and Willis were called in to inspect the organ and report on its condition, in preparation for the claim which the Trustees were submitting to the Government, respecting the occupation. Neither of them had seen an instrument in such a shocking condition. There was, however, one consolation: the organ was basically sound. The Alexandra Palace seemed a useful place in which to wind up the war, one way or another; and, for a good while after hostilities, the building was used for the `liquidation of munitions' - a rather lengthy business, No claim had yet been settled, although the grounds had been re-opened for some time. At length the Palace was handed back. It had been sadly neglected, there having been no adequate maintenance during the period of Government control; and it was not possible for the Trustees to open the building to the public. But, in the meantime, a terrible discovery had been made by the clerk of works. Doors at the side of the organ had been forced and entered; the rooms of the Choral Society ransacked, and sheets of music torn to shreds. But worst of all, the glorious Willis masterpiece, silent for so many years, had been violated. So terribly damaged was it that, when he saw it, the grandson of the builder had difficulty in restraining his tears. The effect on Cunningham was equally distressing. How could it be otherwise? Pipes had been taken and used to bludgeon other pipes as they stood within the organ. More pipes had been hurled through the arch, which is such a feature of the instrument. These were strewn far below, on the platform and out into the hall itself. Along the permanent way from Alexandra Palace station on the GNR to King's Cross, yet more organ pipes and parts of the mechanism were found scattered; for the wicked vandals who had done this thing, and who wore the King's uniform, had entrained with further spoil and discarded it as they went along. Reports in the newspapers, questions in Parliament, action by the military authorities and, finally, the necessary court martial brought this ugly incident to a close. But there was the question of compensation to be settled. A revised claim had, of course, been sent in as a result of the further damage the organ had sustained; but nothing was settled. And all this time the public, having been once again admitted to the Park, clamoured for readmittance to the Palace, and asked questions about the organ. It was hard for them to understand that it was not possible for the Trustees to open a building whose interior reflected five years of utter neglect, and in many cases vicious and obscene vandalism. The neglected roofing leaked all over the place; the woodwork was bereft of paint; the Palace was a scene of the utmost desolation. Gradually money trickled in from the Government. In dribs and drabs it came. And as it came, so it was spent. It had to be; for the Trustees needed income, and this could be obtained only by the resuscitation of those forms of entertainment that had been the Trustees' means of profit in the golden days before the Kaiser's war. It soon became apparent that, since there was now no man alive on the Trust who could take over the honorary management of the Palace, a paid manager must be engaged to run the great undertaking. And so it was decided to advertise. The Trustees were deluged with applicants, and, from the `short list' the choice fell on a man of the theatre, W. Macqueen-Pope, who lived quite near to the Hornsey gate! This was in 1922, and, within seven months of his appointment, the new manager had re-opened the Alexandra Palace Theatre with the Pantomime, Cinderella, as a Christmas attraction. It was no such thing. Money was lost, not only on the pantomime, but on the successive weeks of drama presented by touring companies for some three or four months. The restoration of the Theatre building had, in the first place, cost very much more than would have been needed for the organ restoration; and there was by this time, not even enough to attempt the renovation of the Great Hall in which the instrument stands. The Government ceased payment; and, in the words which became so familiar to us in the `forties, the Trustees had `had it'. They had also spent it. IT IS AN AUTUMN night in 1925. Four rather surprised men are sitting on a platform in a small hall, standing where the Board Room and General Offices of the Alexandra Palace are now to be found. They are surprised because they had not expected so large an attendance at the meeting in which, through the medium of the local press, they had invited interest. The Chairman of the Trustees, who presides, explains why the meeting has been called, and that if those who are present will testify their willingness to serve on it, a committee can be formed to raise funds for the restoration of the organ.... And so the Alexandra Palace Organ Restoration Committee came into being under the chairmanship of the late Mr. G. H. Bower, who, at that inaugural meeting, told the assembly that his father had received a letter from Father Willis, fifty years before, in which the famous organ builder had said '... I am building the, Alexandra palace organ with all my might.' Mr. Bower went on to say that to him - and, he felt, to many others as well - the palace was the place where the organ was. To the young man sitting, with his parents, in the third row, this seemed a true saying: for had he not, when listening to Mr. Cunningham for the first time, been impressed with the same notion? Soon the Restoration Committee was hard at work. Through various sub-committees, it organised whist drives, dances, concerts, organ recitals in London churches and many other entertainments from which it was hoped funds could be raised. But it was a slow business, for these were the years of depression and unemployment which obtruded their canker into the first decades after the 1914 War was ended. Little wonder then that, apart from a few large donations of a hundred pounds or so each, and a promise of five-hundred from the late Mr. Henry Burt - who had been instrumental in saving the Park and Palace for the people of London - voluntary contributions, although enthusiastically offered, rarely amounted to large sums. Now it happened that, shortly after the appeal had been launched, the Nation suffered a bereavement: Queen Alexandra died. It then seemed peculiarly fitting that the restoration of the Grand Organ in the Alexandra Palace should be undertaken as North London's Memorial to the gracious Queen who, during her long life, had so endeared herself to the people of her adopted country. King George V saw no reason to refuse permission, and Lord Cromer wrote: `The King is much touched by the wish of'the people of North London to raise a fund for the restoration of the Organ in the Alexandra Palace, which when completed is to be regarded as a memorial to her late Majesty Queen Alexandra, and His Majesty fully approves of such a scheme.' Everybody was pleased by this gracious message from His Majesty, and by the end of the first year of fund-raising it was decided that so worthy a cause needed a gargantuan effort to bring it to a conclusion. To this end a Great Olde Englysshe Fayre was decided upon; and in every district in North London committees were set up to work for it. And work they did, for more than six months. At length the chosen day arrived, and at three in the afternoon of Saturday, 5th May, 1928, the Lord Mayor of London - Sir Charles Batho - accompanied by the Sheriffs, declared the first day of the Old Englysshe Fayre and Empire Exhibition open. The Empire Marketing Board staged a show in the hall adjoining the Fayre, and their four-thousand-pound effort occupied thirtythousand square feet. For seven days the Fayre and Exhibition remained open; though it would be more exact to record that on each of the seven days it was declared open afresh! The remaining six distinguished openers represented Royalty, in the person of HRH Princess Beatrice; the Empire, through that of the Rt. Hon. L.S. Amery, MP, Colonial Secretary; and Sir Landon Ronald, introduced by the President of the Royal College of Organists, Dr. W. G. Alcock, stood for music. Mrs. Patrick Campbell represented the theatrical world, the Rt. Hon. J. H. Thomas, MP, opened the Fayre on `Everybody's Day' and, finally Earl Jellicoe was the opener on the second Saturday, 12th May; when the British Legion, Boy Scouts, Girl Guides and kindred organisations were present in great force. During the Fayre, Henry Willis 3 exhibited the console of the organ he was building for Brisbane City Hall, in full working order. Amongst the carefully selected demonstrators of this was an ardent schoolboy, destined a decade later to be the organiser of a series of Master Organ Recitals at the Palace - the young Felix Aprahamian. There were also conducted tours over the Grand Organ at certain times of the day. So, midst the welter of rural scenery (hired at considerable expense from a firm in King's Lynn) the true cause of all this anachronistic efflorescence was not quite lost from view. On January 31 st, 1929, Henry Willis 3 signed the contract for the restoration of his grandfather's finest concert organ; but it was, of course, some time before activity on the part of the builders was to be discerned in the Great Hall of the Palace. Work was confined to the factory. At length the instrument was complete in all departments, and its eight-thousand pipes were ready to speak, although there was internal finishing to be done. But the instrument could be heard, and was indeed being played daily by Reginald Goss-Custard, who was a near neighbour and had been a valiant worker for the cause as chairman of the Music Committee. Who more fitting then, to give a demonstration recital to the hundreds of workers who for four years had striven to raise funds for the organ? And what more desirable, that they should be so rewarded for their labours? The recital was an enormous success, and the renowned organist displayed the modernised instrument to perfection. His audience was thrilled and elated beyond measure. But this was not the Grand Opening! That was to come a fortnight later, on Saturday, 7th December, 1929. Nobody present on that occasion can ever forget it. The Rt. Hon. the Lord Mayor of London, Sir William Waterlow, with his Sheriffs, arrived at the South entrance and, having been received by representatives of the local authorities and the Organ Fund, headed by the Chairman of the Trustees, inspected the guard of honour provided by the 7th Battalion The Middlesex Regiment before processing the whole length of the Great Hall. Upon the platform an address of welcome was delivered by the Chairman of the Trustees; and Mr. G. H. Bower invited the Lord Mayor to open the restored masterpiece as NORTH LONDON'S MEMORIAL TO QUEEN ALEXANDRA. The Lord Mayor complied by pulling upon a cord and so unveiling the magnificent new console while, at the same moment, the towering front of the instrument was flooded with light. It seemed a simultaneous impulse that impelled the pliant figure of G. D. Cunningham on to the organ bench, to play the National Anthem. He was there in a trice; and when the anthem was done, there were speeches of thanks. Then the opening recital began. Cunningham had been Birmingham City Organist, and organist to the University of Birmingham for some years; but he had never lost interest in what, to him, was the finest organ he had played in any part of the world. He had been the Palace Trustees' consultant in the matter of the re-build; and Willis had incorporated several of his suggestions in the improved instrument. Therefore, this was a great occasion for the recitalist; just as it was for those who had worked so hard for the past four years. The great virtuoso of the organ was at the top of his form. Playing, as was now his wont, entirely from memory, his programme ranged from Bach's Great G Minor Fantasia and Fugue, to the Fantasia and Fugue on that composer's name, by Max Reger; including on the way: Air and Variations by Haydn (from a Symphony in D); the Finale to the first half, a Wagner transcription, `The Ride of the Valkyries'. Opening the second half was the Introduction and Finale from the Reubke Sonata, while the delicious Scherzo of Gigout was the penultimate offering before the stupendous Reger work brought the great audience to a standing ovation. The Lord Mayor, the Sheriffs and the distinguished guests who supported them, left the Alexandra Palace visibly impressed by their unique musical experience. More glorious than ever before, one of the great organs of the world had been re-born; and the world acknowledged the fact. What had been done to the Father Willis masterpiece to make it yet more outstanding and worthy of note? Henry Willis 3, in a note on the matter, reminds us that: `As built in 1875, the Organ was not only the most outstanding concert organ in the country in point of size, but in design and equipment it was far ahead of contemporary instruments by other builders. ..' and Willis goes on to explain that although it is equalled in the number of its speaking stops by another famous Willis concert organ of his earlier years, that at St. George's Hall, Liverpool, the Alexandra Palace organ `. ..in grandeur of dimensions and of general layout, the fruit of Father Willis's middle period, altogether exceeds the Liverpool organ, or, indeed, any organ of similar size in this country. It has some fifteen more speaking stops than the organ in St. Paul's Cathedral. ..' Now all this is very well so far as it goes; but mere size has often been regarded as a negative attribute in so far as organs are concerned. In the case of this 1875 masterpiece no such adverse criticism could ever be made; and in the restored instrument there were few modifications of the original scheme. The bright, ringing chorus was now reinforced by mixtures and mutations which made it possible to perform music of all periods to perfection. No stodgy Victorian organ here; but a vibrant instrument of music made yet more so by these additions. With crisp electrified action (derived from the electric blowing plant installed in place of the steam engines in the basement), the choir and most of the solo organs enclosed, a console containing every refinement for the player - here was the finest concert organ in the kingdom. Not many weeks were to elapse before Marcel Dupre, giving his first recital at the Palace, said: `. . the finest concert organ in Europe.' His compatriot, the blind virtuoso, Andre Marchal described it as `A veritable masterpiece of all modern organ craftsmanship.' And G. D. Cunningham wrote: `Such a combination of tonal beauty and mechanical ingenuity make the restored and modernised Alexrandra Palace Organ unique.' It was not long before Reginald Goss-Custard, on the advice of G. D. Cunningham, was appointed official organist at the Palace; and, in the years that followed, he gave Sunday afternoon recitals as had his distinguished predecessor in the early years of the century. Occasionally there were special visits of other famous organists such as Marcel Dupre, Helen Hogan, Fernando Germani and G. D. Cunningham. The concerted use of the organ, however, in festivals and with massed bands, was severely limited between the wars, for the Restoration Committee had not raised enough money to lower the pitch of the great instrument. This still stood at C=540; the new standard pitch being C=522, nearly a semitone lower. It was the burning of the Crystal Palace in 1936 that brought the matter to a head, for so many festivals that had been held there were now homeless and the Alexandra Palace had to accommodate them. The Middlesex County Council, as licenser, had already decided that the Great Orchestra of timber was unsafe, and since they were strongly represented on the Trust, contributed about six-thousand pounds to construct a new one and to carry out other safety regulations in the hall. (It is of interest to note that the Lcc had condemned the larger orchestra in the Crystal Palace as a fire trap at the same time. How right they were!) So there was the Alexandra Palace Great Hall with a new Orchestra of concrete and steel, upon which stood the finest concert organ in Europe, still tuned to the old high pitch. Why did not the Trustees do something about it? We must go back a year to find out. In 1936, the Alexandra Park Trustees had been fortunate enough to secure the BBC as tenants on a twenty-one year lease of the South-East wing of the Palace. It was here that the first regular television service in the world was inaugurated. The income of the Trustees then was considerably increased. They were able to plan for the future development of the Palace and Park, by amortising the rents. They even began to decorate the Great Hall, having bought steel scaffolding sections to increase the scope of the works department. The question, therefore, of raising some twelve-hundred and fifty pounds to lower the pitch of the organ never entered the minds of the Trustees as being for a moment possible. But in the mind of one who was not a member of the board, the idea seemed of such importance that some way, surely, should be found to achieve it. It was Anthony Fitzgerald who felt like this; and when this remarkable man felt strongly about anything, he would not be gainsaid. A shy man, small in stature, with finely cast features, he saw to it that his short legs carried him with slow, deliberate steps; for his heart was weak and his blood pressure exceedingly low. He had strained his heart whilst climbing in Switzerland. After a lifetime of teaching, he had been left a chemist's shop by his uncle; and, since he had taken the trouble to become qualified, had run it with the help of a manager. He had now retired. It is necessary to know this much at least, about Fitzgerald; for these were no ordinary times: there were threats of war. And, certainly, Fitzgerald was no ordinary man. He persisted until the Trustees invited him to form a committee to raise the money. They had already pill him in touch with the former organ committee secretary, the late Herbert C. Shaw. `Write to Mr. Barwell,' said he. And so it came about that the author found himself for the second time in ten years a member of a committee to further the interest of the Alexandra Palace organ. This time it fell to his lot to compile a list of members, so that Anthony Fitzgerald might submit them to the Trustees for approval. Soon the Alexandra Palace Organ Emergency Appeal Committee (1937) was born, with the late Mr. T. J. Hewitt as chairman. Mr. R. J. Martin as treasurer, and two Palace Trustees as ex-officio members. These two gentlemen, Councillors George Boulton and E. Stanley Brown, had been members of the restoration committee, before their appointment to the board of Trustees, so were invaluable members of the new body. The untimely death of Mr. Boulton, however, deprived the committee of the privilege of working with him throughout the period of the appeal, and his place was taken by another Trustee, Capt. A. H. Farley. And so it was that with the threat of war around them, this Emergency Appeal Committee of 1937 got to work collecting donations, running a series of Master Organ Recitals organised by Felix Aprahamian, and staging a summer fete in the Grove. Of course it rained on that particular week-end; and the effort was not the financial success it might have been. Nevertheless, by the autumn of 1938, some six-hundred pounds had been raised. It was, accordingly, decided that the Trustees should be approached, to see whether they would consent to a scheme for getting the organ pitch lowered so that it could be used at a grand opening concert in the ensuing summer of 1939; a concert at which it was expected that the balance of the cost would be raised. The plan was soon agreed, and the interest of Sir Henry Wood enlisted. Sir Henry, that great organ enthusiast, entered into the matter whole-heartedly, and - since the raising of money was the object of this opening concert - suggested that it should take the form of a Handel Festival. The appeal committee having already undertaken to provide a suitable choir for the concert, it was not long before the magic name of Sir Henry Wood, coupled as it was with an occasion of outstanding significance, assured that the promise of a chorus of one thousand singers was an actuality. The chorus master was Charles Proctor, the deputy chorus masters were Allan Brown and Myers Foggin; and there were five district conductors. Sir Henry, who gave his services, sought the aid of Professor Stanley Marchant and Dr. George Dyson (they had not then been knighted) in securing the orchestra of one-hundred-and-fifty players from the Royal Academy of Music and the Royal College of Music, of which they were the respective principals. As soloists, Isobel Baillie, Margaret Balfour, Frank Titterton and Harold Williams also gave their services, as did G. D. Cunningham, whose last appearance at the Palace this was. The audience at this concert was great indeed; over five-thousand people from all parts of the country attended. From the platform to the clock, not an empty seat was to be seen, while at each of the entrances many people were turned away. The financial result was all that could have been hoped for: the debt was paid off and there was a surplus of thirty pounds. Everyone was delighted, not least Sir Henry Wood, whose spirit and drive, generosity and enthusiasm will be an abiding memory to all who served the cause. What should be done with this thirty pounds? The question was soon answered, for there was the crying need for a humidising plant to prevent the organ's drying out from the effect of the eighty-six new radiators which just been installed. This would cost thirty pounds; a coincidence which did not prevent the Palace Trustees from proposing to go halves with the Committee in the matter. They asked the Committee to continue in being an advisory body in musical matters, and, of course to supervise the conduct of the Alexandra Palace Festival Choir which, under Sir Henry Wood, was to continue its existence. The fifteen pounds left in the Committee's hands was to serve as working capital for a third series of master organ recitals, four in number. The first three, by Reginald GossCustard, Andre Marchal and Noelie Pierront, took place; but by 17th September, when the recitalist should have been G. D. Cunningham, the Palace was closed: we were at war once more. Cunningham, although he lived until 1948, was never again able to play his old organ. The Alexandra Palace had no part to play in World War Two. It was too vulnerable; and, as a whole, no use could be found for it. For a part of the time the Roller Skating Rink remained open - the only form of public entertainment at the Palace. The new concrete orchestra was useful as an air-raid shelter. The BBC transmitter was in action as a decoy for enemy aircraft. Frequently the Palace was showered with incendiary bombs, all of which were soon extinguished; but there was no direct hit by any high-explosive missile, though there were several nearmisses. All the time the grounds were open to the public, with the bus service running from one side of the park to the other, as usual. From time to time the organ was used for private practice; and on one occasion the Organ Club were permitted to assemble a few members to hear a recital. But, without doubt, the most exceptional occasion was when Norman del Mar arrived to hear a performance of his Organ Sonata, played by one who had been a star pupil of Cunningham, and who had studied the work in question without having had an opportunity of performing it. If only a recording of this performance could have been made: the player was the great horn virtuoso, the late Dennis Brain! In 1944, Hitler's menacing V2, the flying bomb, began to appear over these islands; and one morning, at about 7.30, just as a string of commuters began to enter the Alexandra Palace Railway Station, one roared over the Palace. It exploded between the lake and The Avenue, demolishing the fence and removing the fronts of the houses facing the Park. One intending traveller was blown over a hedge and ended up in a front garden. He suffered some broken ribs. As for the Palace, it lost some more glass, of course: Theatre windows, Skating Rink windows, glass domes and roofs were the chief sufferers. Shingles were stripped from the towers. And the organ? It still stood intact. But the gigantic rose window, immediately behind it, and overlooking the spot upon which the 'doodlebug' had exploded, was completely blown in. And so, with nothing behind it to keep out the rain, and with a severely leaking roof above it, Father Willis's masterpiece was again a victim of war - this time of enemy action. Intact, and unsheeted, it now awaited complete humidisation at the hands of the elements. It was not long before the rains came and did their worst. The sheeting of the windows was, of course, too late to prevent serious damage, though the Clerk of Works set about doing it as soon as he could. With the late Mr. T. J. Hewitt, the writer saw the organ in October 1946. By then the pipes had been placed on the floor of the Great Hall, behind a barrier on the East side. After Henry Willis 3 had discovered a man inside this barrier, industriously sawing wood, the pipes were stored in a really safe place. The years rolled on; Trustees came and went. War damage was met when and where it seemed fitting to do so. All the time, money was being put on one side for the Great Hall, and the Chairman of the Trustees announced that in 1956 they would have enough to begin work. In the meantime, all the plaster from the ceilings of the hall had been removed. It was announced that the organ would be heard when the hall was reopened. New Roofs, new ceilings, new windows and new flooring, with bright paint throughout, welcomed those who attended the opening by Sir Frederick Handley Page. Considerably more than one-hundredthousand pounds had been spent; but it was later revealed that the cost of restructuring the North end of the hall, behind and below the organ, was prohibitive. No seats had been bought, and no carpets; the Great Hall of the Alexandra Palace was, for an unspecified number of years, to be an exhibition hall! In the meantime the organ remained packed away in two rooms, while its front pipes, painted grey upon a crimson case, looked down upon every conceivable activity. Indeed, history seemed to have repeated itself. But, in justice, it must be admitted that the conditions were not the same as those that had deprived the public of the Alexandra Palace organ after the first Great War. This time the money was there; and it was rising costs and increased expenditure on the Great Hall that housed it, which prevented the organ's rehabilitation. Now, once again, came the questioning public. When was the organ to be heard? The Trustees didn't know - that was pretty certain! Somewhere about 1960 they opened another organ appeal, with a dinner at the Palace, at which Sir Malcolm Sargent was the chief-speaker. But this appeal lacked impetus, and was eventually allowed to flag. There was already a sum of money in hand, of course; and it is not without a sense of amusement that the writer recalls obtaining from the Chairman of the Trustees, in 1951, a promise to open a separate account to receive the small balance from the 1939 Handel Festival. The thirty pounds had not been touched. The War had stopped that. The sum had now reached a figure of forty-three pounds, seventeen shillings and eleven pence; and this it was felt that the Trustees should have. So many people had died: Mr. Fitzgerald in the early years of the war; Mr Hewitt and Mr. Shaw soon after it was over. It seemed wise to transfer the amount to the Trustees lest, later on, there should be difficulty in effecting the transfer. But first, the writer felt that he should find out whether the forty-odd pounds could be used for any specific purpose, when eventually the organ should be reinstated. So, to make sure, he visited Henry Willis 3 and sought his opinion. Mr. Willis shook his head and confirmed the suspicion that nothing could be specified. He agreed that the only condition that could be made was that the Trustees should open a separate organ account. That was in the summer of 1951; and by November, the small amount had been paid over, and a written promise received that the Trustees would use it for no other purpose than that of the organ. Some eight or nine years later the Trustees launched their appeal. Was there ever an organ whose welfare has evoked so much sympathy and human endeavour? Indeed, few are the world-famous works of art which have had more concern lavished upon them in so short a space of time. It is incredible that the Greater London Council, who have so recently been entrusted with this noble work of art, should be contemplating its disposal abroad. Standing , as it does, upon a tiered platform, or orchestra, of concrete and steel, with fire-proof artists' rooms beneath (whose demolition will be a costly exercise involving pneumatic drills and oxy-acetylene cutting apparatus) the whole could well be adapted to a hall, slightly reduced in size, and having a balcony. A fitting place, this, for national festivals and the performance of works too big for the Royal Festival Hall. A gathering place for schools and the return of the National Band Festival. All this would enable the nation once again to hear its unique example of British craftsmanship as a recital instrument; while provision for more intimate music making could be provided in an adjacent hall. Oh, let it not be said that the Greater London Council are not so great, after all! Surely they cannot intend to betray their trust? The sale of the Alexandra Palace Organ would be nothing short of this. It must be prevented at once. IVAN BARWELL. LONDON, 1969. `It must be prevented at once.' AND SO IT WAS! When Ivan Barwell wrote those words in 1969, the Alexandra Palace and Park had recently been handed over, by Government decree, to the Greater London Council, which was charged with administering it `... for the benefit of North London as a whole.' Its record was a sorry one so far as the buildings were concerned, though the care of the grounds by the parks department was exemplary. The Blandford Hall, the former ballroom, was used to store paint and varnishes and was suddenly, unaccountably, destroyed by fire. The Racecourse grandstand, a much tougher proposition, was torn down with bulldozers; and the beautiful Victorian bandstand destroyed and replaced with one made of fabric, which was ripped to shreds within weeks. That left the Palace itself, which the GLC was committed to raze to the ground - its friends in the demolition industry were soon aware of this. However, while lead and cast iron were easy to dispose of, the `Jewel in the Great Hall' was the unique Father Willis concert organ, for which the GLC hoped, as with London Bridge, to find a more well-heeled buyer. This meant looking further afield, and was done by advertising, inviting applications from all over the world and hoping, as they did, to get an offer from the United States. Unfortunately for the GLC a great many other people saw the advertisements, were inflamed, and a huge outcry ensued. Among organizations concerned, was the local Ratepayer's Association, of which this writer was then Secretary, which called a public meeting at the Wood Green Town Hall. Although carefully balanced, with speakers for both sides and a completely impartial chairman, the meeting unanimously demanded that the Willis concert organ be kept in this country, and, in the hall for which it was built. Mrs. Joyce Butler, MP for Wood Green asked the Secretary of State for Education and Science ...'if in view of the value of the great organ at the Alexandra Palace, he will take steps to make a special grant towards its restoration as an alternative to its proposed sale by the Greater London Council?' The buck was passed to the Arts Council of Great Britain, which was, later, very helpful, but obviously not sufficiently funded for a project of this magnitude. It was clear that if this musical heritage was wanted, it would have to be fought for, and so in 1969 the Alexandra Palace Arts Society was formed. In an interview with the chief-officer of the GLC, when he was asked by the APAS to explain why the Alexandra Palace organ was being sold, he gave the reason - among others, all proven false - that ...'no-one will come to a hall which has been closed for thirty years.' The APAS disproved this by putting on a concert in 1970 at which Yehudi Menuhin conducted the London Philharmonic Orchestra and a choir of over a thousand voices, in a performance of Handel's `Messiah'. We had the great joy of putting up notices a fortnight before the event, saying `All Seats Sold'! To emphasize the message to the council, the concert was repeated in 1971 and, again, in 1973; by which time, and with a change of chairman, the GLC had accepted that the Palace was wanted by the people, and Ient its full support. 1973 marked the centenary of the building of the first Alexandra Palace, and a group known as the Alexandra Palace Action Group set out to commemorate the event. In order to show the versatility of the Palace, fifty, entirely separate, events were promoted, every one of which was a success. A very moving broadcast by Yehudi Menuhin spread the message of the fate of the Alexandra Palace organ across the British Isles, and was repeated over an American network. Meanwhile, with a change of council, the GLc now supported the retention of the Palace and promoted its own concerts, as well as setting up an Advisory Board to help in the running of the Palace. Now that the home of the Willis organ was thought to be assured, attention was turned, once again, to restoration: Willis's estimate for this, in 1970, was in the region of £70,000 and it was believed that the money would be forthcoming from a prominent musical charity. However, at that time, the GLC would not entertain any work being done and did, in fact, sell the instrument. After two abortive sales, it was finally purchased, on behalf of the Nation, by Henry Willis 4, great-grandson of the original builder. This was to the great relief of the instrument's supporters, for this would ensure that the Willis family would be responsible for the work when finance became available. Pipes from the organ had been stored in two large rooms at the North end of the Great Hall, into which vandals had broken, causing considerable damage. It was also found that workmen, repairing the roof, had allowed hot tar to drip through into the parts of the instrument below, so Henry Willis 4 started to remove as much as possible for safe-keeping in his own workshops. The next decade was to be a period of political in-fighting: Although the GLC was now responsible for the running of the Palace and was, indeed, promoting events there, it had determined that the organ must go, to make more space for exhibitions (which were the most profitable events in the hall). The situation arising from a great deal of false information being disseminated both locally, and in Parliament, was brought to a head by a letter from the then Prime Minister, himself an organist of repute, who had been advised that the organ was beyond repair. Following this, letters were sent to all members of Parliament to give them the facts. Also, to give proof of the quality of the Alexandra Palace organ, EMI produced a long-playing record made from pre-war 78 r.p.m. recordings. This was quickly sold-out and was later released as a`Classic'. This of course silenced all those who said the organ's quality was only ...`old men's memories'. As councillors and committees were convinced in turn, so changes in councils, chairmen and political persuasion made it necessary to begin all over again. So often, the people charged with the administration of the Alexandra Palace, had never visited it and knew nothing of the organ. In 1980 came another hammer-blow: A fire at the Palace destroyed the West and Central parts of the building, this included the Great Hall and the `shell' of the Willis organ. Some people thought that this was surely the end of the story, but it was, in fact the beginning of a new, and far brighter, chapter. At a public inquiry held to determine the future of the burned-out building, in overwhelming majority of speakers declared that the Palace must be rebuilt; and nearly all insisted that the famous Willis organ should be restored and replaced there. However, it was clear to most people that, if the organ were to be restored, those who wanted it would, yet again, have to find the money. There was now no doubt that the organ was wanted and the new controlling authority, the London Borough of Haringey, responded positively. After all, the Council was composed of local people who knew the Palace for themselves, and were in touch with the people who were pressing for its restoration. In this new, healthy climate, the Alexandra Palace Organ Appeal was launched in 1982, by Yehudi Menuhin, and a number of fund-raising schemes begun; the most successful of these was the `Adopt a Pipe' scheme, under which, over a thousand people paid for the restoration of a pipe. Added to this, the Alexandra Palace Board agreed to match, pound-for-pound, any amount raised by the appeal committee. The immense amount of work was broken down into stages, each of which could be completed as and when the money became available and, in 1985 the restoration commenced at the Willis factory in Petersfield. While work proceeded at the Palace - rebuilding the Great Hall together with the adjoining halls and rooms - and in order to keep the site alive with visitors, a temporary but large pavilion was erected, in which functions took place for many years until the beautifully refurbished Great Hall was ready. The great day for Alexandra Palace organ supporters came, in 1990, when the partly re-built organ sounded for the first time in public; here was proof that the restored organ, in the re-built Great Hall, would again produce the matchless combination which had brought fame a century earlier. WHAT IS THE PICTURE Now? A beautiful two-hundred acre park in North London, rises on a hill, at the top of which stands a century-old `Palace for the People'; its familiar outline remains unchanged, while its interior has been transformed by modern standards and materials. It contains one of the finest multi-purpose halls in the country, supported by adjoining halls, Palm Court, foyer, a superb restaurant and many refreshment areas. But the jewel in this setting is a British musical masterpiece, the Alexandra Palace Concert Organ, and more and more people are becoming aware of this. It is not yet complete, but those who saw, and heard, it in the 1991 and 1992 tea-time concerts had a foretaste of what it will be, when completed. The work WILL be completed when funds are found, and so, every effort is being made to bring this chapter to a close. Then, a new, brilliant chapter will open on the fascinating story of "The finest Concert Organ in Europe". FRED CLARKE. LONDON, 1993. |

|